Hail readers! As promised, here is mine and Oli’s essay on Socialism. Read on for a detailed look into Socialism’s philosophical, moral and economic underpinnings; an argument concerning its validity and place in 21st century Britain; and, to finish off, a debate on the Labour leadership contest.

Socialism, Defined

The question that many a political novice fails to ask is one of ‘What, exactly, is Socialism?’ This is in fact a question with no definitive answer—thinkers have used the word to mean many different things, across various time periods and nations. But we can, at least, define what we mean when we say Socialism.

To me, Socialism is a political and economic theory based on the core idea of, simply, ‘we are not alone’. A Socialist views the world not necessarily through the lenses of ‘proletariat’ and ‘bourgeoisie’ (though these ideas have their merits) but rather, we tend to take a more pragmatic view: we believe that a democratically elected state can—if its citizens are willing and its administrators competent—improve the lives of the citizens it cares for, to great effect. We believe that capitalist markets are flawed, but that they can be made more successful with judicial state intervention; that all citizens have the right to equal opportunity; and that through our collective endeavour, we may make the world a better place.

Really, the clue is in the name. Capitalism has an administrative focus on capital—profit, usually monetary—whilst Socialism lends more attention to society itself: to welfare, primarily, which becomes inclusive of education, infrastructure, and so forth, further down a line of successful administration. What Socialism is not is also an important part of its definition. It is not Communism by any default (although Ideal Communism, with its focal point being community, is indeed a form of Socialism, whilst Actual Communism perhaps is not). Such distinctions allow me to state with clarity that Socialism is not oligarchic, so let’s lie that to rest immediately.

Oli’s point is an important one: many Conservatives attack Socialists for being ‘statists,’ but in fact Socialism doesn’t view the state as being an end in an of itself. Rather, Socialism takes the view that the state is a tool of the grassroots community; that it is there to serve their interests, not dictate to them like some drunken bureaucrat. Socialists are also accused of being ‘technocrats’; and this is true, insofar as both wish to advance mankind in some form. In the case of Socialists, this is usually—though not, as you can see, necessarily—through the state; for technocrats, it is through technology. Since the two are far from mutually exclusive, technocrats often agree with Socialists.

Socialism is about cooperation—between citizens and the state, one state with another, and citizens amongst themselves. Communication and cooperation is perhaps technology’s most impressive feat. This very article is being written simultaneously by the two of us sat miles apart.

It is also no secret that Socialism acts on a moral impetus, not merely a broad technocratic one. Many Socialists—like Capitalists, in fact—are Utilitiarian; we view the state as a creation capable of increasing society’s utility, of improving life. It is also true, however, that Socialists are concerned with poverty and social justice—sometimes, to the possible detriment of Utilitarianism. It could be said that Socialists have a vision: that of creating a society where relative prosperity is available to all. Interestingly, however, the principle of decreasing marginal utility may actually imply that a more egalitarian society—as Socialism desires—is actually also a more prosperous society overall, despite mean wealth being lower than a comparable ‘Capitalist’ state. (Though, as I shall argue below, Socialist nations may actually be wealthier than Capitalist ones.)

But is it Convincing?

Interestingly, Conservatives usually don’t argue that Socialism is undesirable; that they would, in an ideal world, be Capitalists rather than Socialists. No—the usual dismissal is that Socialism is ‘too unrealistic’ or, rather ironically when coming from Conservatives, ‘too idealistic’.

With regards to the latter, the argument is usually that Socialism simply cannot achieve the social justice which it sets aims for. In part, this is resultant of varying aspects (or entirely different definitions) of what social justice is. The already-mentioned egalitarian approach of creating equal opportunity to counteract socio-economic circumstances which may hold individuals back seems a perfect ideal, but in practice is such a complex process of individual assessment that it can drain public resources to no large effect. The benefits system we have today can be viewed as an example of a bureaucratic nightmare wasting money at every turn. The problem here is that such governmental wastefulness is in itself a social injustice. Of course, without such a system, poverty, starvation, illiteracy, death and disaffection would be all the more common— it is therefore also an example of Socialism coming before Capitalism in a society which contains both.

A noteworthy issue with strict egalitarianism (which Socialism is often and wrongly labeled as) is that such a system may deny meritocratic funding of talented individuals, whilst spending ‘too much’ to bring the less able up to the same level of ability. In Aristotle’s words, “To the best flautist goes the best flute”. In another analogy, if society provides a training carpenter with tools, will not the most talented apprentice make best use of the tools—or better use of better tools? In turn, this service from society is an investment in society, as the carpenter will improve in his carpentry. Without meritocracy in some capacity, mediocrity becomes prevalent throughout society as a whole. Strict egalitarianism (though not that of opportunity) may well deny society the chance to advance.

In summary, the Conservative spiel is that meritocracy and egalitarianism are both ideals of justice, but are in contradiction. Which do we adhere to, and if we synthesise, where lies the balance? Inequality of opportunity is arguably an unjust natural occurrence, but amendment of this using public resources can be viewed as equally unjust, if not in principle then in practice. In essence, social justice is paradoxical, and attempts either creates a social divide through meritocracy (therefore missing its goal) or makes mediocrity prevalent (unjust and non-progressive). Therefore, we are told, Socialism will revert to Capitalism, to pragmatism, after failing to balance the books of the impossible ideals, which perpetually contradict and require spending to do so.

The lie is of course that Socialism is always portrayed as an ultimatum, always as entirely this or entirely that. As Alex will point out, we already live in a somewhat Socialist society. The purpose of this essay is perhaps to convince readers of why we ought to be more Socialist—and why they ought not shrink from the word. The truth is that there is a middle ground; we can support the impoverished whilst supporting the talented. Just by deciding to do both, we’ve bridged the gap that has been invented. The whole point of Socialism is to address social issues, rather than to gamble on a market of utility to sort them out for us. Of course we can, and we should. For those doubting if we ‘can afford it’, I hand you over to Alex:

Economically, Conservatives propose a number of arguments for why they believe Socialism cannot work (or work well); and chiefly among these is the idea that, since a state must rely on taxation to fund many of its enterprises, a Socialist society would lead to individuals having less ‘incentive’ to be successful—due to, of course, being unable to keep more of their money. Thus, a Socialist society becomes impoverished when compared to its Capitalist counterpart.

Conservatives, you see, believe that high rates of taxation result in individuals (always the individuals) obtaining less benefit from extra work, and so not wishing to work more, or become more successful.

The problem with this argument is that it ignores the other side of the coin—that, by lowering individuals’ net income, it is actually the case that individuals wish to work more in order to achieve the level of wealth they find desirable, as opposed to remaining content with what they already have. Conservatives also fail to consider the varied reasons for why individuals strive to become wealthier; in the case of entrepreneurs, it is to pursue a dream, a vision. Entrepreneurs are a rare class of the damned; they’ll never be content with the nice life.

And if you’re inclined to disconsider all these theoretics as mere speculation, consider instead the conclusions offered by empirical data: why is it that Japan—a government with relatively low taxation levels—has very similar GDP per-capita to Germany, a country with relatively high taxation levels? Both were severely damaged after WW2, and yet their wealth is entirely comparable. Surely, if taxes have such significant disincentivising effects, wouldn’t there be much larger differences?

Another popular right-wing myth is that without reaching a Communist state (which many wrongly consider to be the logical conclusion of any leftist movement), Socialism is too reliant upon inherently unstable conditions (human cooperation without capital incentive) to not revert back into Capitalism. Indeed, this is exactly the argument made by Karl Marx in the Communist Manifesto, this the foundation of his call to arms of the proletariat. From the Conservative perspective, then, Socialism is futile, a pointless endeavour, whilst from the Communist perspective, it is a stepping stone that sinks if you don’t cross it quickly enough. Talk about pessimism!

As Alex illustrates, the basis of such arguments are simply false, and Socialism therefore can stand on its own, in its own right. In fact, compared with other quasi-capitalist nations that pertain to the far-right ideals, such as China, we are already Socialists. We are already illustrating my next point: Socialism, for us and many others, is not anarchistic, but stabilised by a familiarly democratic electorate. By redirecting the wealth that capitalism has gained us, we can become more Socialist and less Capitalist—invest in society rather than in more capital.

Oli has also illustrated another fundamental misconception that troubles thinkers of both political stripes: believing that the state only redistributes wealth, as opposed to creating it. This is patently false. Such thinkers confound money—a proxy used as a denominator for the exchange value of goods—with what wealth actually is: the utility gained by the production of goods. For example: when a carpenter makes a table, his life becomes better. Why? Well; because he has a table. He may place his tools, his books, his plethora of miscellany on top. He has created what we know as ‘wealth,’ or what the classical economists call utility. Utility, you see, is fundamentally metaphysical in its nature; it cannot be represented by money. Money is only a quantitative abstraction representing what other agents are willing to exchange for the table, e.g. two shirts of linen.

And the state does precisely this sort of ‘wealth creation’ when it, for example, builds bridges; treats broken bones; and teaches children. This is wealth creation. The reason why the state taxes is because otherwise there would be inflation; and there would be inflation because of what is known as opportunity cost—since labour is finite, employing workers to, for example, treat an eye condition implies that there are no workers left to build a Mercedes as well. Thus, when the state taxes a wealthy individual, all it does is match the money supply to resources by keeping the money supply constant; a drain to the money supply (taxes) is matched by an increase to the money supply (paying NHS nurses).

Another economic argument presented against Socialism by critics is that of ‘competitiveness’; in an almost apologetic tone, the Conservatives tell us, if we become Socialist (by which they really mean to say ‘if we increase welfare’) then we will be unable to compete with China.

After the argument is made, the debate often becomes one of globalisation; ought we really engage in free trade if we are forced to make such sacrifices? The argument concerning globalisation is a complex one; and indeed not the one I shall be making. Rather, I argue that if we wish to be competitive, we should be Socialists—precisely because it allows us to be more competitive.

‘But Alex!’ you cry; ‘how can this be so? Surely, as the Conservatives tell us, Socialism would make us less competitive?’ The trouble is, Conservatives rely on a number of argument for why they think Socialism is uncompetitive—or, rather more accurately, why they think Socialism is inherently inferior to Capitalism insofar as the economy is concerned. I have already debunked one such claim concerning taxation, and another with regards to the role of the state. Against global competitiveness, I shall abandon theoretics, and instead content myself with empirical evidence.

China is a big country. A big, big country; it has 1.3 billion people, in fact. Curiously, however, Germany—a country with ‘just’ 80 million people; less than a tenth the population of China—is able to export approximately two-thirds as many goods (by international exchange value) as China. Why is it that a country with high levels of unionisation, safety laws, and yes, welfare, is able to produced ten times as many goods (in terms of value) per capita compared to a country with little welfare, laughable safety laws, and low unionisation? Why is the Socialist country beating the Capitalist country?

For that matter, why is it that the European Union—which has 500 million people—has greater total wealth, and far greater prosperity, than a nation with 1300 million people? Despite, it seems, taxing more, and spending more?

What determines competitiveness is nothing to do with the nebulous insinuations of the Conservatives—of welfare leading to fecklessness and laziness. No: competitiveness is determined by such factors as an educated workforce; a stable and well-run financial system; capital availability; infrastructure, competent leadership, and, believe it or not, a society where every member contributes to its success.

Many of those feckless poor are actually poor because of such factors as unemployment—and not because they don’t want to work, but because there is no work—because of disability or sickness, and because of social problems. None of those will be solved by cutting benefits; on the contrary, doing so will aggravate the problem. Nor is this to say, however, that benefits are the solution. The poor need education and training, but businesses must also be willing to hire them; and social problems are a complex issue that require solutions far beyond what the market can offer. Indeed, all of these problems are beyond the market’s ability to solve. And so, you see, it is precisely why we should be Socialist; if not for the goodness of our hearts, then for the money in our pockets.

As for the goodness of our hearts, once it becomes apparent that Socialism is possible, it seems to me inarguably the right thing to do. The message of Socialism is of compassion and justice—that we can do more towards both for every member of the state. For me, the mere fact that we can leads to say that we should.

And now we hear the Libertarians cry out in the face of Socialism (read: Actual Communism). “We can’t let the state command resources, make social and economic decisions on behalf of us all!” Rebuttal: we’ve already explained this is not what we are talking about. The purpose of the Socialist state—arguably the ideal purpose of any state—would be to provide what all members of society already desire: a minimum standard of living and a shot at success. Capitalism claims to provide both, gives moderate attention to the latter, and miserably negates the foremost. The Socialist state is not authoritarian, and does not control personal decisions.

Let us now leave the matter of Socialism as a theory—for which, suffice to say, if we have not convinced you already then we never will—and instead deal with another matter: how to bring more Socialism to Britain.

Labour, Leaders, and FPTP

It is no secret that first past the post is a voting system that allows the voter but two choices: Left, or Right? And, inevitably, any pretence of nuanced thought gets left by the wayside. Though this essay is concerned with Socialism, we believe the matter of FPTP is important enough to merit a sidenote. Indeed, it could be argued that successful Socialism cannot function without successful democracy.

FPTP

There are two alternatives to first past the post: the foremost is a form of proportional representation practised in Germany, and involves a complex system of vote-transfers between constituencies; the second, as practised by Denmark and numerous other nations, is a simple raw vote count—independent of regionality—from which parties are permitted to elect members to the Parliament.

Our own local MP, Nadhim Zahawi, has criticised PR of the Danish variety, on the basis that it endangers “links with constituency”. Whilst a valid point, this is a non-issue if we maintain constituency voting.

The Devil’s Advocate that I am, I must take issue with this. Yes, we may keep constituency elections for a second house of Parliament; but the first house—that of the national government—remains subject to a different issue: MPs being elected on the basis of ‘party favourites’ rather than their ability to sway the electorate.

Coincidentally, PR is working quite well for Germany; their government consists of one third PR by default, theoretically giving everybody a proportional representation. Meanwhile they maintain regional representation to form the other two thirds. It’s not perfect but it’s an example of a working PR system: a more honest spread of opinion, and undeniably more democratic than FPTP.

Alternately, I would suggest a completely different solution—fix the party, not the system. British political parties are too authoritarian; too much weight is given to the leader and the Cabinet, and not enough to ordinary MPs and grassroots members. This not only leads to ‘party favourites,’ but also to internal tension and strife. (This can become so poisonous as to lead to open rebellion; Major’s bastards and Blair’s Brownites serve as prime examples.)

Party democracy is possible—The Green Party have no whip, leaving members to openly discuss policies and even to disagree with them. Some consider this a leftist practice, but why shouldn’t other parties behave, well, democratically? To Zahawi, we say improve the system at every opportunity, right down to the parties themselves.

FPTP also has the obvious benefit of producing ‘stable governments’—strong majorities in parliament. Indeed, it was created for this very purpose. Coalitions are viewed as inherently ‘unstable’ in the UK. I consider this an outdated opinion for a number of reasons; 2010 resulted in a coalition (which I consider preferable to the current government); 2015 polls were incredibly tight until the end; so-called ‘minor’ parties such as UKIP have soared up the raw vote figures but remain near-unrepresented; and nearly an entire nation of the UK is now represented by a ‘minor party’. With all this divide, the Conservative party may have a majority in parliament, but achieved a mere 36.9% vote share of a 61% turnout. That is 22.5% of the populace. Where is the stable majority in these raw numbers? We have riots and protests because huge numbers of citizens are not represented at all thanks to the FPTP system.

Furthermore, what critics of PR fail to understand is that British political parties are coalitions. One need only look at the Conservative party (where Cameroonians battle Eurosceptics) and the Labour party (where Corbynites war with Blairites) to understand the phenomenon. Indeed, PR would therefore result in more stable governments; factions of a party, instead of fighting WW3 with one another, would instead agree to co-operate under the set terms of a coalition.

And we have already seen that coalition works, not only in the UK’s 2010 government, but around Europe. All bar one of the post-WWII German governments have been coalitions, and their economic (and social) success has already been referenced in this essay.

So: let’s ditch FPTP. Let’s embrace a modern, representative, and effective democracy.

So: You Want us to Vote Labour?

As long as we suffer under FPTP, Labour is the logical choice. That’s not to say you can’t vote for another left-wing party if they better represent your views—it is simply a system failure that only Labour have a realistic chance of enacting your views in Parliament. But this still leaves a decision to be made and a vote to be cast: Labour are leaderless after Ed’s resignation. So, who to elect to leadership?

As far as I’m concerned, Labour needs to win, in order to enact change. But that doesn’t mean it must abandon its principles; on the contrary, it is principle that will make the party strong—both at election time, and when governing.

To win, Labour must confront the reasons for why it lost. Here are five ways it can do so:

‘Labour didn’t fix the roof while the sun was shining.’ Throughout the election campaign, this remained unchallenged. Milliband made apologies; he did not repudiate, he did not offer a counter-narrative, and he was weak. This must change. Though Labour may accept a small degree of culpability only in that it could have run a more fiscally sound administration (though Thatcher actually borrowed more, for example), it must make one thing very clear: the banks caused the crisis. It must spin its own narrative—and it must be a relatable, accessible one; abstracts won’t do it. ‘The banksters gambled the nation’s bank accounts,’ would be a start. In politics, offence is the best defence.

Their policies need to appear sensible. This isn’t to say that they are not sensible—our entire essay is hopefully illustrating just how much sense there is in Socialist thinking. The problem is that abstract talk of “grotesque inequality” and “class war” (let alone “bourgeoisie”) is simply not as effective as concrete talk of “the squeezed middle” and “the 1%”. It’s one thing to speak of class war, another to say ‘Why must the single mum at Asda struggle to pay the rent, while banksters can’t decide on whether to buy a Mercedes or a Bentley?’ The fact is that Labour did not sell themselves anywhere near well enough in the last election. There is too much of the abstract about them, it seems too fluffy—they need to clearly state the problems in society, and what they will do about them.

Scotland. Labour needs to deal with the SNP Problem. And no: denigrating the SNP, or making what ultimately amounts to minor administrative quibbles (about NHS waiting lists and so on) won’t do it. Labour needs to make a strong case for why Scotland should stay in the Union; it needs to be rational, yes, but also emotive. Look to Gordon Brown.

Immigration. Labour needs to sort out the immigration problem. How? Not by peddling to UKIP; but by making a convincing, impassioned case for why the UK should allow immigration.

And finally, the European Union. Labour’s stance is clear but they still need to make the case for staying, as passionately and as sensibly as for all the above issues. Labour needs to seize upon the Conservative and national division on the issue so that by the time the referendum comes about, the right decision is made. Ed Milliband should have promised the same as the Green Party—a referendum, but with strong campaigning to show people the benefits of staying and the damages of leaving. The decision to not have the conversation with the nation probably lost thousands of votes. The decision to have it now will help win thousands back.And of course, Labour musn’t just speak sense; it must speak passion. ‘If we leave, we’ll be not just Little England, but lonely Little England,’ might be a start.

The success of the right wing in recent times has spun off of public perception of words such “socialism” rather than their genuine meaning. It has been focused on a narrative that is understandable, relatable, and accessible. The left, meanwhile, has clung to its principles and used them as a shield, seemingly without realising that these principles are misunderstood, and without offering good explanation. Such issues as these can only be addressed in education and in the disarming of biased media, but both are a long way from their ideal states. Their lack of clarity has lost them 2015, not their lack of conviction, nor the principles themselves.

As for who should be leader? Let’s start with a rundown of the current candidates:

Andy Burnham: A centre-left candidate; he voted against IVF for lesbian couples and he has the support of the unions. In some ways, he’s a continuity candidate; but he also talks about popping ‘the Westminster bubble’ and he has a Mancunian accent (or is it Scouser?) He is willing to appoint Corbyn to the Shadow Cabinet, or serve under him if he gets elected. Note that his aides backstage wrote this off as a joke.

Yvette Cooper: a ‘centre candidate,’ Yvette has spoken on the possibility of re-introducing the 50% tax rate, and plans to build 250,000 homes. She is Shadow Home Secretary, and has a good record on civil rights. She has said that she would consider appointing Corbyn to the Cabinet, though she wouldn’t want to serve under him.

Liz Kendall: Coined as a ‘Blairite’ by the media, Kendall wouldn’t raise the minimum wage, but would work to ‘persuade’ employers to offer a ‘Living Wage,’ and would introduce requirements on minimum wages for companies that have government contracts. She has also said she would free up more land for housing. She says that if Corbyn got elected, the Labour party would be ‘at least a decade out of power’ and that she would not cooperate.

Jeremy Corbyn: A left-candidate, Corbyn has proposed to introduce a £10 minimum wage; to not renew Trident; to bring in the 50% rate; and to nationalise the railways, among other policies. For the Green supporters among you, these were all in their 2015 manifesto. He says he would ‘find common ground’ with all the candidates, including Kendall.

Jeremy Corbyn has been called ‘unelectable’ by the Guardian, and a ‘Trotskyite’ by the Telegraph. It feels almost redundant to say that such accusations are absurd (Trotsky despised democracy; Corbyn is a firm democrat) but there is one point that must be addressed here. A party doesn’t get elected by selling policies in the manner befitting of a corporation; it gets elected by convincing a large portion of electorate that their way, is the right way.

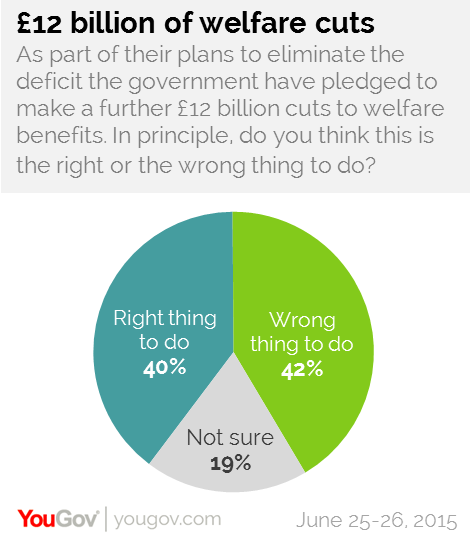

It is true that it is very difficult to convince the electorate of one’s policies if one’s policies are directly against most of the popular opinion. And yet—despite whatever the media tell you—Corbyn’s policies aren’t against the popular opinion. Quite to the contrary, in fact.

Apparently, the public also supports a 75% tax on incomes above £1M (YouGov ) a mandatory living wage, and nuclear disarmament. (Independent)

But let us discuss some of these policies…

Nuclear Disarmament: After much debate, we have decided that we disagree with Corbyn’s policy insofar as we wish to keep a nuclear deterrent—though not necessarily in the form of Trident.

The spending on nuclear weaponry—let’s not tread softly with words, here—in this country ought not exceed the values necessary for the upkeep of a deterrent. We make this statement on the careful analysis of what we consider the weaponry to be for; we certainly hope that, as a nation, we harbour no intention to actually use a nuclear weapon on another nation. So why create an offensive force, rather than invest only enough to maintain a deterrent?

In an ideal world, Corbyn would be right, and we would lead the way to nuclear disarmament by scrapping our spending and research into the area entirely. This would rest upon faith in other nations to be equally peaceful and responsible. (It would be ridiculous to assume that all other nuclear nations would follow suit immediately.) The question we must ask, then, is can we trust them? Russia, under the ultra-nationalist control of Vladimir Putin (and cronies), is a very real threat. China is often less than friendly and rather erratic. Let’s not forget the various extremist factions around the world, nor the bizarre but terrifying antics of North Korea’s dictatorship. If there ever will be a time to completely lower our defences and lead the way to peace, perhaps this is not it.

Of course, there may well never be an ideal time for the first step to be taken—for the first nuclear nation to resign from nuclear activity—simply because the world may never be safe enough for any one nation to step out into the abyss. We then considered whether or not we could place a transnational platform over the threat of destruction for the first nations to stand upon.

For this, I would suggest setting up an ‘EU Defence Fund’ in which all EU member states pay for the upkeep and construction of a small, but sufficiently credible, nuclear defence system. The specifics would be for military experts and other EU politicians to discuss—likely this will involve trans-continental missiles, submarines stationed in Sweden or Denmark, and upkeep paid according to GDP—but this solution would be cheaper for us, and fairer for the EU.

Corbyn’s policy is ultimately unrealistic, but I will point out that in today’s world, there is nobody whom you will agree with completely; and, practically, the Labour party would never vote to scrap Trident, even if Corbyn does become leader. We are glad that the matter is being discussed, or progress would never be made.

Corporation Tax Increase: Another issue that presented itself was that of Corbyn’s plan to increase corporation tax. Though we are not opposed to increasing taxes, I for one consider this particular tax rise counterproductive and misguided. Allow me to elaborate…

Corbyn has presented a vision for the economy; one that involves high economic growth, supported by investment—not cuts. But for high levels of investment to occur, businesses must be able to keep their profits; if they cannot, they will have none with which to invest.

It is true that the additional government revenue could be used to invest—in roads, rail, education, and all manner of valuable causes. But we are not communists; we live in a world where private firms, as well as government enterprise, contribute to the economy. We need private investment, as well as government investment, in order to succeed.

What Corbyn should really be tackling is high rates of executive pay in relation to the pay of other company employees; and while increased income taxes, for example, can be beneficial in generating increased revenue for the government (Corbyn indeed plans to reintroduce the 50% rate) this fails to address the root cause of much of inequality—a neoliberal, ‘winner-take-all’ corporate culture that disempowers the many in order to remunerate the few. We need to change the very way today’s corporations think; we need increased rates of unionisation (as Sweden has, for example) and ways to address CEO bonuses. ‘Tax, tax, tax,’ may be a popular Socialist mantra, but it shouldn’t be the only one.

Corbyn’s issue is the issue shared by the public image of Socialism itself. There is a more detailed, delicate and effective way to manage our economy, to achieve the justice which is being aimed for, than simply increasing taxes. In fact, this is the likely root of the unfortunate “we can’t afford it” criticism. That said, taxes play a roll, and all in all, Corbyn seems to be looking in the right direction —the left one.

National Insurance Tax Increase:

In brief, I consider this a good move, if only because Corbyn’s plan is to spend the money on making education free. University tuition is accessible to pretty much everyone at the moment, with a generous loans system that can cover everyone’s costs. There are problems, however, which make these loans a temporary fix in my eyes.

Firstly, whilst the tuition fee loans de facto make the tuition available upon request, the maintenance loans fall short of the mark on numerous occasions. The household income assessment is an unfair basis because it assumes a household is willing to—or can even afford to—support a child living at university. This is only worsened in families with multiple children, where the income of the household is stable but the expenses go up and up for each successive child attending university, without any extra help relating to the fact that they have more children. Clearly, more money needs to be spent to help people attend university—or at the very least better calculated.

Secondly, education simply should be free. Education is a right, but it is not equally accessible. The recent scrapping of student grants and the continuation of the student loans enforces a principle: those with less initial wealth will spend longer with less wealth. Those who can afford University initially will benefit from it faster. This is is unfair. It is punishing the poor simply for being poor, in the name of education. It’s disgusting.An old metaphor may best be adduced here: ‘A wise man places the heaviest burden upon the strongest of shoulders.’ Education is a public investment in the future of a nation, and with the push since Blair to get more students in Universities, it is ludicrous to charge them all for it as well.

And let’s not forget, Oli, that even tuition fees for ordinary students have been introduced with an agenda at play. The Coalition government wouldn’t raise the marginal tax rate; but it did triple tuition fees—precisely in order to make the less well off (namely, recently graduated students just entering the job market) pay more of the burden, instead of older graduates and better paid graduates.

The Right may respond ‘but shouldn’t students pay for their education’ to which I respond: not necessarily. For, after all, it is the rich that benefit most from an educated workforce. Apple wouldn’t exist if universities didn’t train computer science graduates; retailers would struggle without the roads designed by state-schooled engineers; and it is therefore only sensible to make the rich pay for universities, not because of envy, but because they are the ones most able to pay for the system that so enriches them.

So is Jeremy Corbyn Right?

My answer is: yes and no. Jeremy has a vision—a real alternative to neoliberal austerity programmes; and, more than that: he’s right on so much. He’s right on tuition fees, he’s right on nationalisation, and he’s right that Labour shouldn’t become Tory-lite; if not for principle, then for electoral success.

He has his flaws. He’s too keen to tax, tax, tax; he speaks too much in the abstract, with ‘grotesque inequality’ rather than Polly at Asda and bankers buying Bentleys; and on some of his policies—nuclear disarmament, foreign policy—he’s too idealistic.

Ultimately, he has the right ideas. He speaks of an alternative that the other candidates are too shy, too self-doubting, to speak of. So: the ideas are right. But is he the right man to sell them? He stutters (albeit occasionally), he speaks in the abstract, and he doesn’t always have the necessary pragmatism. So, no, he isn’t. Is he more likely to win the election than, say, Cooper or Burnham? I’m not sure. Will I vote for him? Yes. If none of the candidates will succeed in bringing Labour to power, then at least we will have a strong opposition.

As for me… Yes. He’s the right leader for the party. What lost Labour the election wasn’t it’s Socialist leftism, which Corbyn represents very well. As Alex talks about, there are flaws in his ideas, but for all the reasons Alex illustrates I would support him over the others. But perhaps Corbyn is the right man at the wrong time. In 2015, the Conservative party were well situated after a reasonably successful coalition which they took more than their fare share of credit for, and the preceding disappointing term of Gordon Brown. All of this was spun into a cohesive narrative of deficit cutting, rising employment, et cetera, as a part of an admirably well orchestrated (and incredibly expensive) campaign, which reacted to the political climate influenced by Labour’s divide, the SNP phenomenon, and the pressure-oven that is UKIP. Labour can recover from this anti-leftist climate if they campaign well—we’ve already discussed this. But perhaps Corbyn would be too far a leap right now.

Personally, I’d vote for him anyway. That’s me, I’m an idealist, I think politics is about moving towards our ideals. It is for his vision that I would feel compelled to vote in favour of Corbyn. I wouldn’t change my vote because Cooper may be more likely to succeed, because I believe in the message that Corbyn is offering. The success of the party ought to come second to what the party stands for. As Tony Benn once said, in politics, there are weathercocks and signposts—true and tall and principled. Socialism and leftism are, in their simplest forms, about principles of justice, welfare, and compassion—all combined with a little common sense.

Whatever the outcome of the leadership contest, I will give the winner one word of advice: politics isn’t about aping your opponent. It isn’t about ‘matching the electorate’ or selling goods to consumers. It’s about conviction. A strong leader must speak with charisma, in a language voters understand, and they must always hold true to what they believe in. To compromise is to be pragmatic; to capitulate is to accept defeat before the battle has even begun.

Contact Oli Woolley: email woolleyoli AT gmail.com, or contact him on Twitter and Facebook.