Owing to substantial interest from my readers, I am bumping up this post—and including additional data. If you wish to comment, please do so below; and apologies for my lackadaisical blogging efforts as of late. The Ark is growing steadily...

A strange malady seems to have overtaken the Labour party. Some call it ‘Corbynmania’; others call it, more simply, ‘madness’.

But most call it ‘hope’. And it is indeed the majority who decided the fate of the Labour Party that Saturday—let us not forget that. So: what are we to do?

Certain wings of the party—notable proponents include Simon Danczuk, Chuka Umunna and Liz Kendall—are reluctant to move forward. ‘This is madness; we will be annihilated; what disaster has befallen us!’ they claim.

Absurd as it may seem, their claims require careful consideration in order to be proven, or—as I will show—disproven. And we cannot ignore them; if not for preserving ‘party unity’ then for a more simple reason: they may have a point. If Jeremy cannot keep the party together, if his policies are not workable, or if—most importantly of all—he cannot convince the wider electorate to vote for them, then the Labour party must be prepared.

A relative minority of Corbyn supporters have expressed support for the idea that, even if Corbyn doesn’t do very well, he would at least have stood fast to principle. To this I say: rubbish. Power without principle is anarchy; but principle without power is a pipe dream. If some form of compromise is indeed necessary, we owe it to the people we represent—not just the disabled and the poor, but also the millions of middle-income people fooled by the Tories—to win power.

But are such grave compromises really necessary, and is Corbyn the unelectable disaster some profess him to be? Let’s take a closer look.

Renationalisation etc.

One of the matters that Corbyn is rather popular on—despite claims made by ill-informed media commentators—is in his idea to renationalise the railways, the Royal Mail, and to a lesser degree the energy companies. I previously quoted polls conducted by YouGov in my analysis of Socialism, but it is worth re-iterating them:

Interestingly, we see that not only are Corbyn’s policies popular among his own party and other vaguely left-leaning parties like the Lib Dems (as well as the SNP, etc.); but that they are popular in general, and significantly by UKIP voters and even quite a few Tory voters.

So: Corbyn’s not going to have any trouble pushing that through.

A similar story may be found with regards to renationalising Mail and Energy:

So, on the basis of public opinion, Corbyn is not going to have any difficulty finding supporters for his renationalisation policies. However, there is another question to be had here: is it actually a good idea to renationalise, and if so, how can this be achieved?

Let’s start with rail. The case is overwhelming: since privatisation, railway ticket prices have increased 22% (adjusted for inflation); subsidies have increased, but most of the money has gone directly into shareholder’s pockets; and the UK has rail prices that are as much as double those of nationalised European nations. (We Own It)

Furthermore, it is estimated that simply by not having to pay shareholders, the government could chop off 18% from ticket prices. (ibid.)

Nor can it be argued that the railway companies provide better service: the average age of the trains has gone up; and to add insult to injury—they are more overcrowded, too, with only a 3% increase in carriage capacity to meet a 60% rise in demand. (ibid.)

Renationalising them isn’t complicated either. The UK state still owns much of the rail infrastructure, and the companies run the trains on franchises; when they expire, the state can run them once more.

The energy companies—known collectively as the Big Six, and owning over 95% of the marketshare—have also increased their prices by between 40% and 20% (for gas and electricity respectively) since 2007, despite seeing a tenth-fold rise in profits within the same period. (We Own It) The latter is particularly damning: while the global price of gas varied significantly at that time, the substantial rise is down mainly to companies pocketing a healthy profit.

Indeed, Corporate Watch even calculated that nationalising the energy companies would serve to bring savings of £150 a year to each household, on average. (CorporateWatch)

But how are we to nationalise them? This is where Corbyn gets into some difficulty. Buying the companies at market rate is out of the question: it would cost £185B (TheGuardian) He could theoretically impose price freezes, regulation on passing down the cost of falling gas prices, and so on; this would lower their stock value, allowing these companies to be bought cheaply.

That, however, is no way to run good government. More likely, Corbyn can attempt a municipal system of state ownership: municipalities can run their own power stations, and charge their customers accordingly. Alternately, the state could simply buy one company, and let the others go out of business. That’s capitalism for you.

Welfare, And Other Tricky Matters

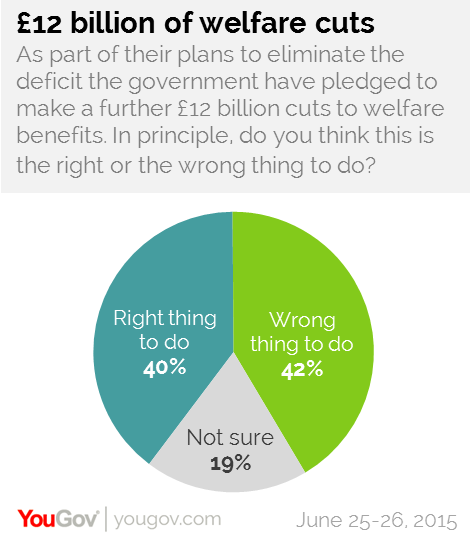

This is perhaps where Corbyn may fall. The public’s opinion on welfare seems rather divided:

However, the situation is not so simple as it looks. For one, a lot of opposition to welfare in general stems from certain assumptions—apocryphal ones:

The amount of misinformation presented to the public, and supported by the Tories—implicitly or explicitly—is remarkable. One woman believed the Tories to be the party of the poor, and Labour... not so. She also apparently believed that the rich shouldn’t pay more tax—evidently the trade-off was not clear: if you support this, you will pay more tax yourself, or you will face cuts to the NHS. (In fact, the Tories have done just that—by scrapping tax credits.)

A pair of women believed that the Labour party supported the ‘scroungers’—people who don’t want to work, and want to stay on benefits.

Liz Kendall was right to point out that the Labour party has a serious problem: the public believes Labour to be the ‘something for nothing’ party. But Kendall’s response wasn’t the correct one. The solution is not to feed into this nonsense; not to agree that the ‘scroungers’ are stealing the taxpayer’s money (fact check: fradulent benefit claims make up 0.7% of the welfare budget (ONS)) or that Britain is facing some imminent crisis on welfare.

Because Britain is facing a welfare crisis, and that’s the one created by Iain Duncan Smith: his regime is responsible for the deaths of thousands. (TheGuardian)

Still, there are turbulent times ahead. Getting Labour’s message out to the public, and killing these apocryphal rumours where they stand—well, it won’t be easy. Perhaps it would be easier to compromise. But it wouldn’t be the right thing to do; at least not if compromise requires near total capitulation, as seems to have befallen Kendall.

Trident, NATO, and Other Matters

I shan’t be discussing these matters overly much. I have already stated that I disagree with Corbyn’s foreign policy, on my Socialism essay; but I’m not so presumptuous as to think the public are wise enough to agree with me. The media commentariat evidently needs to get out more—the polls tell a story very different from their narrative...

The public are opposed to extending the bombing campaign on Syria... Source: The Independent

Jonathan Knott, over at OpenDemocracy, is also worth quoting with regards to how much voters actually care about NATO and Trident...

So 55% supported retaining nuclear weapons in some form. But given that before they were asked specifically about Trident, about a quarter (23%) didn’t know whether the UK had any nuclear weapons or plans to replace them, it’s hard to argue that this is a high priority for voters.

This ComRes poll also has an interesting tale to tell... Apparently, voters mostly agreed with the statement: ‘Nuclear weapons are too expensive for governments to maintain.’

The public also seems quite amenable on other aspects of Corbyn’s policy, including support for the minimum wage and rent controls...

Immigration

Readers have enquired as to why I omitted a section on immigration; the answer to this is: it simply did not cross my mind at the time. I am, generally speaking, not particularly concerned about immigration—nevertheless, as with many issues, I do not presume to be in the majority. The public’s views on immigration are somewhat complex; it’s worth taking a look at a lot of the data.

Firstly, the picture very generally appears to be that the public feels negatively about immigration—in economic terms particularly:

(It seems almost superfluous to mention that nearly all economists—like those from the Imperial College, or the National Institute for Economic Research—have come to the conclusion that immigration is positive for the UK economy; opinion triumphs knowledge, it seems.)

Nevertheless, the picture is more complex than this. For one, more people believe that refugees should be allowed in as opposed to not (48% versus 38%); further, more people believe that NHS staff from abroad should be allowed in as opposed to not. (YouGov).

As usual, I feel it necessary to bring some facts to bear. A lot of people are under the impression that immigration has dramatically increased in recent years, for example:

With Farage’s and Cameron’s rhetoric, it’s not hard to see why. But as is sadly all too often the case, this is not what is actually happening—at least not so simply.

Source: Migration Watch

While net migration has been unusually high this year and the year before, it was significantly lower between 2011 and 2013; lower even than the years previous. Why? Finding the exact causes would require more words than I’ve time for—but, likely, we are seeing both statistical variation (notice the variation in the early 2000s and in the 80s?) and the effect of one of the largest refugee crises in recent history. The NHS also saw significant shortages of qualified medical personnel, which perhaps explains another part of the equation.

So: how would Corbyn fare in this matter? It’s hard to say. Corbyn is pro-immigration, yes; but if he would be able to convince others of his point of view (as good politicians are meant to) then this may not prove a problem. Further, it is hard to determine exactly how this would sway an election result—a lot of people are concerned about immigration, but are they not also concerned about unemployment, financial security, and housing? And what exactly are the other parties going to be offering in that dimension?

UKIP only won one seat—so voting for them is unlikely to result in any meaningful change—and their policy on the economy ranges from the merely very stupid (like flat tax: if you earn £16K and have lost your tax credits, prepare to pay more tax—just like the banker on £150K!) to the absolutely moronic (like scrapping the NHS—or has Farage changed his mind yet again?) The Tories are trying to make millions of people £££ worse off, and their housing policy is responsible both for the enormous increase in house prices (by subsidising demand, and and not regulating banks) and for the shortage (by not allowing councils to build houses, among other things). The Liberal Democrats promised to do a lot of things in 2010, like getting rid of tuition fees. Instead they tripled them. If you can’t trust them to fulfil their most important promise, why trust them with anything else?

But I digress. On immigration, Corbyn is, for once, in the minority. Nevertheless, there are a number of other issues to contend with—not to mention the vagaries of the FPTP system.

To Conclude

This post has been rather detailed and indeed rather lengthy. But a clear picture emerges here: Corbyn is not unelectable—his policies are popular, especially on the economy (the living wage, rent controls, and renationalisation) while even his more contentious foreign policy is far from the fringe position the commentariat makes it out to be. Indeed, Corbyn is more often that not with the majority.

Is this to say the sailing will be smooth? No. As I said before, Corbyn isn’t a man full of charisma; his ‘authenticity’ may go down well, but he is less than prime-ministerly. Don’t think this matters? Look at Miliband. Many of his policies were popular too, but he failed to win; if he had possessed better personal ratings, we (probably) wouldn’t have a Tory government.

Nor will things be easy on welfare: there is a widespread misconception of what the situation is really like, and on what the Labour party stands for. And let’s not forget the parliamentary Labour party, too; there’s quite a bit of opposition there, sometimes with reason (in the case of printing money, or leaving NATO, or on Eurotoxicity) but not always—as Danczuk and his ilk show.

Still, there’s reason to hope. The country is far from the right-leaning, NATO loving, Tory-lite image that the likes of Rafael Behr and Jonathan Freedland would have you believe. The Tories are a minority, after all; and many Tory voters aren’t Osbornomicists—but people deceived by misinformation on welfare, on immigration, and on what the Tory party really is. (Hint: they lowered inheritance tax for millionaires and cut tax credits for working people. They sold off the Royal Mail at knock-off prices to their chums in the City. Who the hell do you think they are?)

So to all this, I say: Labour, get ready to fight. Blairites, shut up—or Labour won’t get elected, and it’ll be your fault. Corbyn? Get a tie.